I am a fan of memes. To me, they represent who “we” are in a very real sense. After reading Ratcliffe, I guess I need to solidify who I mean by “we” (ooh, did you see that rhetorical listening I just did on myself?). By “we,” I guess I mean affluent, predominately white, educated, plugged-in (or digitally literate), young, American males obsessed with pop culture and inside jokes. So you very much may not be included in that group; but you might be, even if you aren’t an affluent, white, educated, plugged-in, young, American male obsessed with pop culture and inside jokes.

So let me start over. I love memes because I identify with those who are most likely to create, distribute, proliferate, and engage with them. I am a big fan of Know Your Meme, a for-profit website dedicated to cataloging and discussing memes and their implications in culture. I check it every once in a while, probably just to see what “my people” are thinking about and saying and whether or not I agree or disagree. Perhaps my own interaction with memes is mostly about identity building.

And so, maybe that is why I was primed to see this particular meme, “The Unhelpful High School Teacher” (or click the images in the gallery below to see a few instances of the meme) as a site of cognitive dissonance or a “margin of overlap” (66), as Ratcliffe calls it. My body has been troped, or marked, as a white, internet using, pop-culture obsessed American, but also as a teacher, and this meme represents a place where these two tropes are in conflict with each other. Which cultural trope am I supposed to side with? The inside-joke-loving, witty, participator-in-memes? Or the sincere teacher trying to be the best teacher I can be? If I am a meme-er (I just made that up), than I am engaging in an act that recognizes teachers as hypocritical, self-absorbed and stupid. But if I am a teacher, I could easily resist the messages in the meme and fail to recognize the validity of memes as culture. I could just say that the meme creators don’t understand teachers and are just spoiled anonymous kids sitting safe behind a computer their parents bought them. But by doing so, I am imposing false stereotypes on the group as a whole and turning my back on a group I identify with. So what’s the solution?

Eavesdropping.

If I “[choose] to stand outside… in an uncomfortable spot… on the border of knowing and not knowing… granting others the inside position… listening to learn” (Ratcliffe, 105), I can learn from these memes without becoming defensive, or insulting the tropes I identify with. I can listen to the memes instead of defensively rejecting them outright. I can step outside of my roles as teacher and meme-er for just long enough to see the validity of the Unhelpful High School Teacher meme as culture and as constructive critique for all teachers.

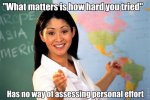

For example, one instance of the meme (which is known as an exploitable, meaning it is an easily distributed image, which those who participate in the meme download and use various programs to add text to) quotes a fictitious teacher saying “‘What matters is how hard you tried'” at the top of the image and then “Has no way of assessing personal effort” at the bottom, is one where a margin of overlap happened for me. The top line of the meme is the setup and observes a typical behavior a teacher might do or say, and the bottom line is the rejoinder, which points out the hypocrisy or absurdity of the teachers behavior. When I listen rhetorically to this instance, I am faced with the very real truth that I have no way, or a very arbitrary way at best, of assessing personal effort. I have to humble myself and hold myself accountable for those accusations of hypocrisy and ignorance.

In an 2010 article in Composition Studies, Kerry Dirk points out that what some professors call a “Participation grade” is not really based on any real system to back it up, but is rather used to fudge grades one way or another based on a subjective feeling the teacher has for the student when it comes time to assign grades. So there is some very real truth to this internet meme and one that I need to now deal with as a teacher. However, without rhetorical listening, I would be forced to cling to one trope or the other and deny and defend (and possibly insult and harm), or simply feel internally dissonant looking at these memes.

When I rhetorically listen though, I don’t have to give up my role as a teacher to defend the validity of memes, and I don’t have to give up my role as a teacher to defend the integrity of other teachers like me (which is really just a way of defending myself and my own actions) by questioning the validity of memes or those that create them. I can be both at the same time by giving up both for a small amount of time to just listen. I can then begin the process of figuring out a way to assess personal effort, or else change find new motivation to unpack what I mean when I say (or think, or portray) that only personal effort matters. Rhetorically listening isn’t an end in itself, it is a gate that we walk through that requires more work after passing. But it also gives us a way as teachers and people to let go of tropes that cause conflict and listen in a way that can bring understanding.